The recent partial derailment of a freight train on the vital east-west rail corridor north of Port Pirie in South Australia has once again underscored the critical importance of this transcontinental link. The incident, which caused extensive damage to the line, disrupted services between Sydney and Perth, Melbourne and Perth, as well as Adelaide and Darwin. This disruption has prompted renewed calls for the Federal Government to increase investment in this essential piece of national infrastructure.

A History of Vulnerability and Vitality

This is not the first time such appeals have been made. In 2022, heavy rains in South Australia inundated large sections of the Trans-Australian Railway, bringing rail freight services into Perth to a complete standstill and placing significant pressure on supermarket supplies. These events serve as stark reminders of how reliant Western Australia remains on this steel thread connecting it to the eastern states.

The dream of linking east and west was a monumental challenge long before the Trans-Australian Railway from Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta was finally opened in 1917. A commemorative booklet issued on November 12, 1917, and held in the State Library of Western Australia, reflected on how the railway made real the phrase "a nation for a continent and a continent for a nation" coined at Federation in 1901.

An Island Continent Divided

Before its construction, Australia was described as being like "two great islands — an eastern and a western." For nearly all practical purposes, Western Australia was as completely separated from the Eastern States as New Zealand. The only land link was the telegraph line running around the coast of the Great Australian Bight. Travel between east and west meant a sea journey of over a thousand miles.

The commemorative booklet traced the idea of a cross-nation link back to June 1840 when the Agricultural Society of Western Australia's chairman raised a plan from South Australian inhabitants to open a road. This idea met with fierce opposition and was rejected on grounds of "impracticability and the undesirability of making a road to enable bushrangers... to make raids upon this Colony."

The Explorers and Visionaries

In 1841, explorer Edward John Eyre became the first European to cross the Nullarbor Plain during an arduous four-month journey with his Aboriginal companion Wylie. In 1870, WA explorer and later premier John Forrest led a west-to-east crossing, including much of the country near the later railway route.

According to the commemorative booklet, it was the "marvellous growth in the population, wealth, and importance of Western Australia, beginning with the great gold discoveries (in the 1890s)... which first brought the idea of a railway to link up the two sides of the Continent within the range of possibility."

The Political Carrot of Federation

An Engineers Australia report notes that Forrest was among the first politicians to publicly promote an east-west transcontinental railway. In 1888, he suggested its construction should be a condition for Western Australia joining an Australian Federation. The John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library states that in 1896, when a railway line reached Kalgoorlie from Perth, Forrest promised Goldfields residents the railway would not stop there.

"Thus the lure of a trans-continental railway did become the 'carrot' which led WA to join the Federation of Australia," the library notes, adding that this was only a promise, not a guarantee, resulting in years of lobbying before fruition.

From Survey to Steel

After Federation, Forrest entered the Commonwealth Parliament and in 1904 introduced the Trans-Australian Railway Survey Bill. Survey work began that year, with Western Australia surveying from Kalgoorlie to the border and South Australia from Port Augusta to the border.

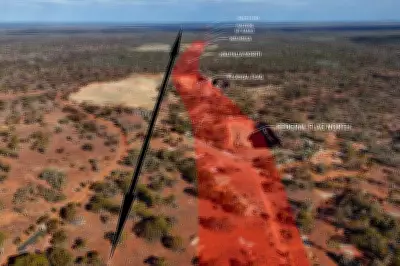

Richard Anketell led the Western Australian party, which included three other surveyors, ten camelmen and assistants, and 91 camels. Anketell set the alignment by compass, checking it by stellar observations and marking the route with a heavy 'snigging chain' drawn by a camel. The South Australian survey party, under J.T. Furner, faced the heat of summer before reaching the border cairn in March 1909.

Construction Commences

Following a visit by Lord Kitchener in 1911, the Federal Parliament recognised the railway's importance for national defence. A vote for the new transcontinental railway passed on December 6, 1911. Construction of the 1,692 km standard gauge railway from Kalgoorlie to Port Augusta began in 1912.

The first sod was turned by Governor-General Lord Denman at Port Augusta on September 14, 1912. The West Australian hailed this as "an event of immeasurable significance to Western Australia, indeed, to the entire Commonwealth," noting it represented "the first instalment of a long outstanding Federal debt."

Engineering Against the Elements

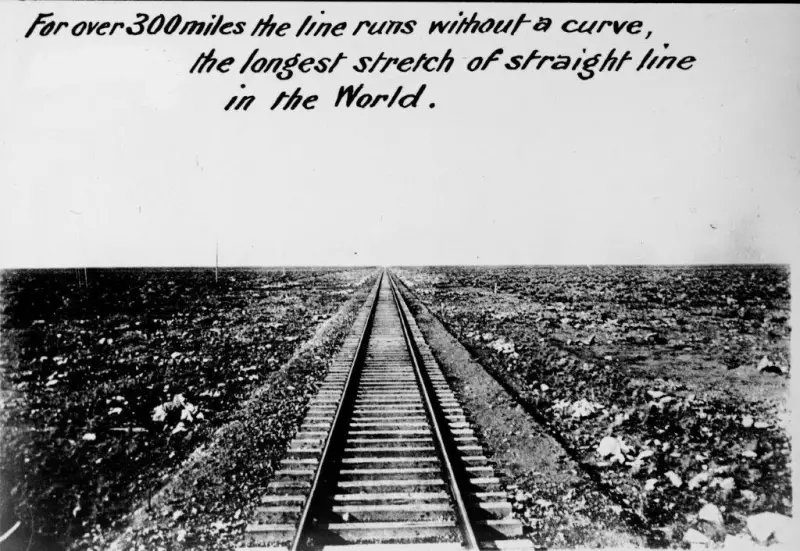

More than 1,030 working drawings had to be prepared, with tenders called for railway equipment, locomotives, wagons, and construction materials. Almost all mainline track was laid using two track-laying machines imported from the United States, with teams establishing Australian records that stood for nearly 50 years.

Crossing the Nullarbor in summer, temperatures often exceeded 45°C in the shade. Work was scheduled for early morning and late afternoon as steelwork and tools became too hot to touch. According to the National Museum of Australia, it took five years to lay the 2.5 million hardwood sleepers and 140,000 tonnes of rail needed.

The Final Spike and a New Era

The last railway spike was hammered into place outside Ooldea in remote South Australia on October 17, 1917. Five days later, the first passenger train set off from Port Augusta, arriving at Kalgoorlie 42 hours and 48 minutes later.

On October 18, The West Australian reported the line's completion, quoting Forrest's statement that he had longed for 25 years to link east and west. "Western Australia, comprising one-third of the continent, hitherto isolated and practically unknown, is from today in reality a part of the Australian Federation," Forrest declared. "From today east and west are indissolubly joined together by bands of steel, and the result must be increased prosperity and happiness for the Australian people."

Ever pro-Western Australia, Forrest suggested in vain that the line be named the Great Western Railway. The railway immediately cut mail delivery from Adelaide to Perth by two days, and eastbound travellers arrived in Melbourne three days earlier than by ship.

Legacy and Modern Significance

In 1969, the standard gauge network was extended east from Port Augusta to Sydney and west from Kalgoorlie to Perth, enabling train travel from the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean. This led to the naming of the Indian-Pacific passenger train that now runs along this historic route.

The recent derailment serves as a contemporary reminder of this infrastructure's enduring importance. What began as a political promise to secure Federation, fought for through decades of lobbying and constructed against formidable environmental challenges, remains today a vital artery for national commerce and connectivity, its historical significance matched only by its continuing practical necessity.