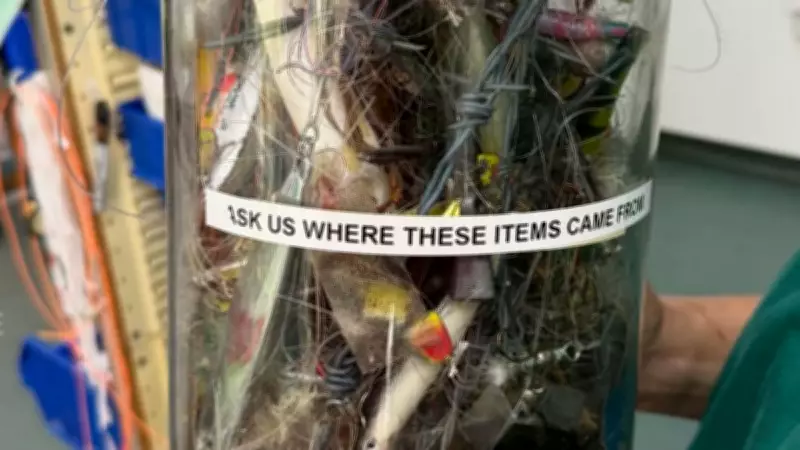

A prominent Australian wildlife hospital is confronting visitors with a chilling visual display: a large glass jar, packed to the brim with fishing lines, hooks, and assorted plastic fragments, accompanied by a sign urging, "Ask us where these items came from." The sobering answer, revealed upon inquiry, is that every single piece was surgically extracted from the internal organs of injured animals.

An Invisible Crisis in Queensland

Currumbin Wildlife Hospital in Queensland has deployed this jar as a powerful educational tool to shed light on what senior veterinarian Andrew Hill describes as an "invisible" menace plaguing local wildlife. According to Hill, injuries from fishing lines and hooks rank as the second most frequent cause of harm to animals, trailing only behind collisions with vehicles.

"It's an invisible problem," Hill explained. "Fishing line causes some of the worst injuries that we treat, but they're also some of the most preventable." Birds and turtles are particularly vulnerable, often ingesting or becoming entangled in discarded gear.

A Jar That Speaks Volumes

The hospital typically empties and refills the jar every three months, but during the bustling six-week summer holiday period, it can become completely filled. This visual aid is aimed at reaching the estimated 70,000 recreational anglers in southeast Queensland, who, research from Queensland University indicates, invest over $400 million annually in fishing equipment.

"The hook jar is there because it can do the one thing we can't: communicate effectively the size of the problem," Hill noted. During warmer months, as outdoor activities like fishing and boating increase, the hospital admits up to 120 animals daily, with fishing-related injuries appearing almost every day.

The Devastating Impact on Wildlife

Hill expressed frustration over the cyclical nature of the issue. "We can do the ambulance work and try to fix these animals up, hopefully, and send them back out, but we feel really bad having to fix them and then send them back into the same situation," he said.

Entanglement in fishing lines can lead to severe consequences, such as cutting off circulation or damaging nerves and blood vessels, potentially resulting in the loss of limb or wing function. "It's really distressing when you find these animals are being tangled for a long period of time," Hill added. "The wildlife has to live on, they don't have a choice. So often they'll live for sometimes a year with lines trailing off them."

Plastic Peril and Migratory Birds

Beyond fishing gear, plastic pollution poses a significant threat, especially to migratory species like shearwater birds. As these birds commence their migration around Australia Day, they frequently mistake plastic debris for food, leading to fatal ingestions. "We have birds coming in that are literally crunchy when you pick them up because their stomachs are full of plastic," Hill revealed.

How the Public Can Assist

Hill identifies the top threats to wildlife in the region as car accidents, pet attacks, and fishing-related injuries. He emphasizes that behavioral change among people is crucial for a solution. "It's a people problem, it's a behaviour change that actually is the solution," he asserted.

To mitigate the issue, Hill advises against feeding birds at fishing spots, as this attracts them to hazardous areas. If encountering an injured animal with a hook or line, he cautions against removing or cutting the line yourself. "If there's fishing line coming out of a bird's mouth, I can actually use it to guide us to the hook with our endoscopes and we can prevent having to do surgery," he explained.

For those wishing to help, Hill recommends:

- Contacting a wildlife centre for guidance.

- Safely transporting injured animals to a local vet clinic, using items like towels or boxes stored in your car.

- Avoiding handling dangerous animals such as snakes or flying foxes, and prioritizing phone support to ensure personal safety.

Ultimately, prevention is paramount. "If people now take steps to reduce the amount of tackle that's going into our environment, it can actually dramatically improve the health of our wildlife," Hill concluded, underscoring the collective responsibility to protect Australia's native fauna from these preventable harms.