Australia's long history of royal commissions, marked by a pattern of inaction and political point-scoring, should serve as a stark warning against launching another one into the Bondi Junction shootings, argues columnist Crispin Hull.

A Track Record of Disappointment

Since 1980, Australia has held 26 royal commissions, yet their collective record in addressing the core issues they were meant to solve is poor. According to Hull, these inquiries have consistently failed to remedy the underlying "sins, wickedness, and malfeasance" they investigated.

Despite public calls for a royal commission into the Bondi tragedy as a cleansing act, past form suggests it would likely be another drawn-out, expensive exercise with minimal practical impact. Hull points to Prime Minister Anthony Albanese's tendency toward secrecy and opacity, suggesting his government could not be trusted to be fully transparent or to implement recommendations that might challenge its political or financial base.

What Past Inquiries Tell Us

Examining the types of inquiries a Bondi commission might cover reveals a discouraging precedent. Since 1980, Australia has seen four royal commissions into security and intelligence, yet their effectiveness is questioned by recent events. Similarly, six major inquiries into the mistreatment of vulnerable groups—including aged care, deaths in custody, and child sexual abuse—have largely told the public what it already knew without stopping future abuse.

Even the celebrated royal commission into the Chamberlain case, which proved Lindy's innocence, did not fix the systemic issues of junk science in courtrooms or police tunnel vision, as later cases like Kathleen Folbigg's demonstrate.

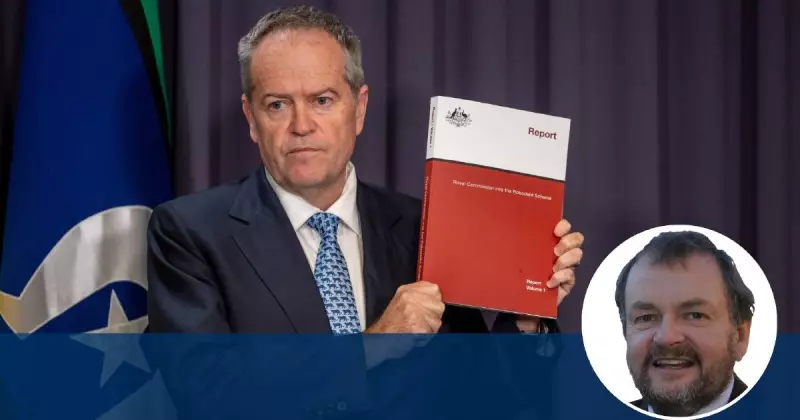

Politically motivated commissions have fared no better. Three inquiries into union corruption failed to weed it out, while the 2014 home insulation commission found no systemic wrongdoing. The robodebt royal commission, despite blistering evidence, resulted in no personal punishments and left whistleblowers singed.

The Call for Action, Not Another Inquiry

Hull contrasts the call for a royal commission with the decisive action taken after the Port Arthur massacre in 1996. Then-Prime Minister John Howard, who enjoyed public trust, took forceful action on gun laws without a lengthy public inquiry. The columnist argues the real task now is to fix and constantly review gun laws, not embark on another legalistic process.

He also warns against opportunist politicians using the horror to push for populist, nativist immigration policies, distracting from the core issues of housing, health, and infrastructure strained by high migration levels.

Ultimately, Hull concludes that while public pressure may force a royal commission into the Bondi shootings, it will likely do little to stem the underlying evil of anti-Semitism or prevent future violence. The mechanism itself, he suggests, is an outdated appeal to a higher authority that rarely delivers lasting change.